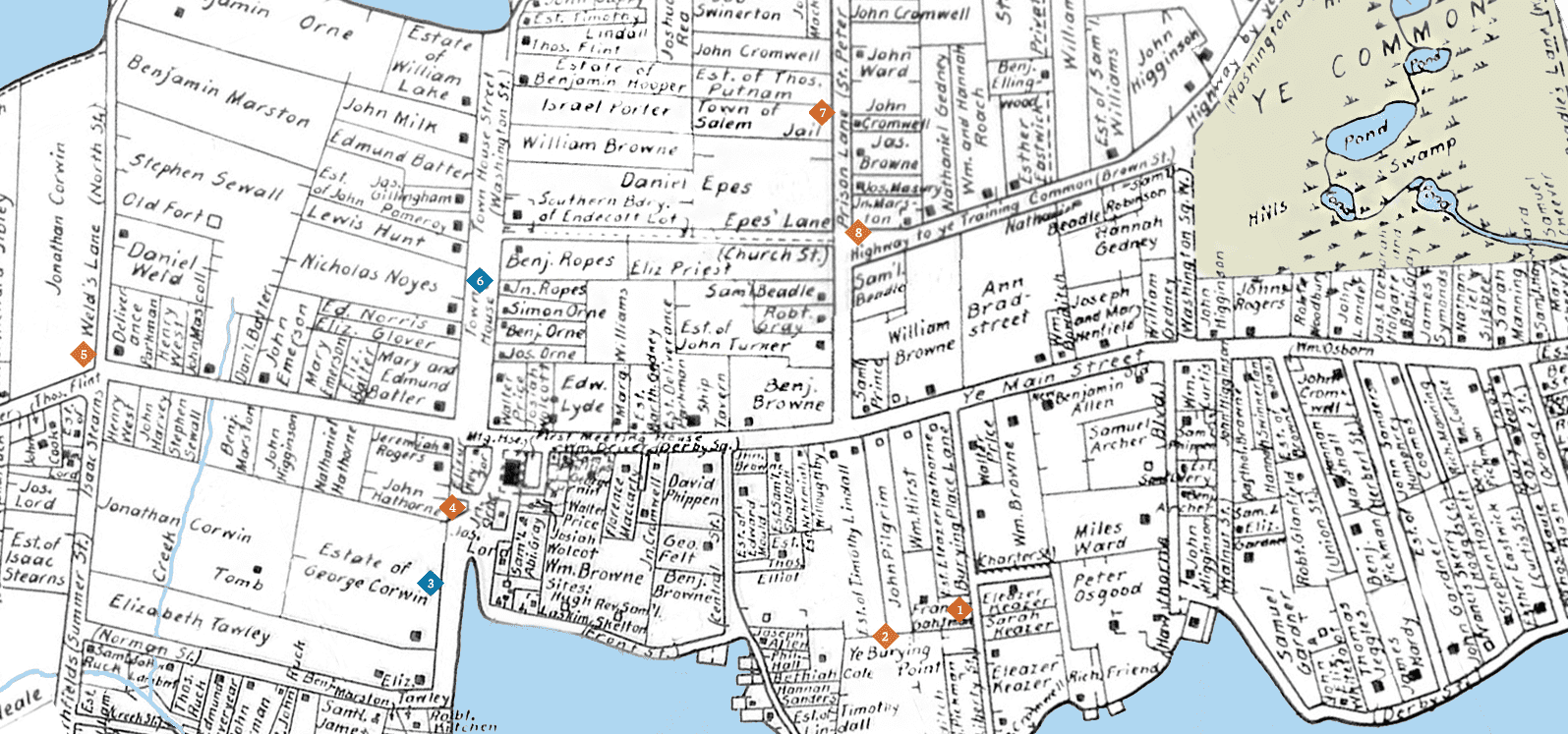

Compare this map with the modern map in your booklet. This historical map shows Salem’s layout during the time of the Witch Trials, allowing you to see what has changed and what has remained the same in over 300 years.

“SALEM” Witch Trials? Where did it happen?

The Salem of 1692 bore little resemblance to today’s city boundaries. What we now call “Salem” was actually a vast territory encompassing multiple present-day municipalities: Salem, Peabody, Danvers, Middleton, and portions of Beverly and Topsfield. This expansive area housed approximately 2,000 residents, divided between two distinct communities with very different characters.

Salem Village was a rural farming community of about 500 people, characterized by agricultural settlements, family disputes over land inheritance, and growing tensions with the more prosperous Salem Town. The village was marked by economic struggles, boundary disputes, and factional conflicts that would later play crucial roles in the witch trial accusations.

Salem Town was the commercial center with roughly 1,500 inhabitants, featuring a bustling port, merchant class, and more cosmopolitan atmosphere. The town’s prosperity and political influence created resentment among the rural villagers, contributing to the social tensions that helped fuel the crisis.

Beyond Salem: A Regional Crisis

The most significant misconception about the 1692 witch trials is that everything happened within the boundaries of Salem. In reality, the accusations spread like wildfire across Essex County and beyond, creating a regional panic that affected dozens of communities throughout eastern Massachusetts and parts of Maine (then part of Massachusetts).

Modern Perspective

Today’s Salem, with over 45,000 residents, has transformed into a bustling city that capitalizes on its witch trial history through tourism and cultural attractions. However, this modern focus on Salem obscures the historical reality that the 1692 events were a complex, multi-community crisis that reflected broader social, economic, and religious tensions throughout colonial New England.

Understanding the true geographic scope helps explain how approximately 200 people could be accused, 30 found guilty, and 20 executed in a population of only a few thousand spread across multiple communities. The trials weren’t an isolated urban phenomenon but rather a regional breakdown of social order that exploited the interconnected yet fractured nature of Puritan colonial society.

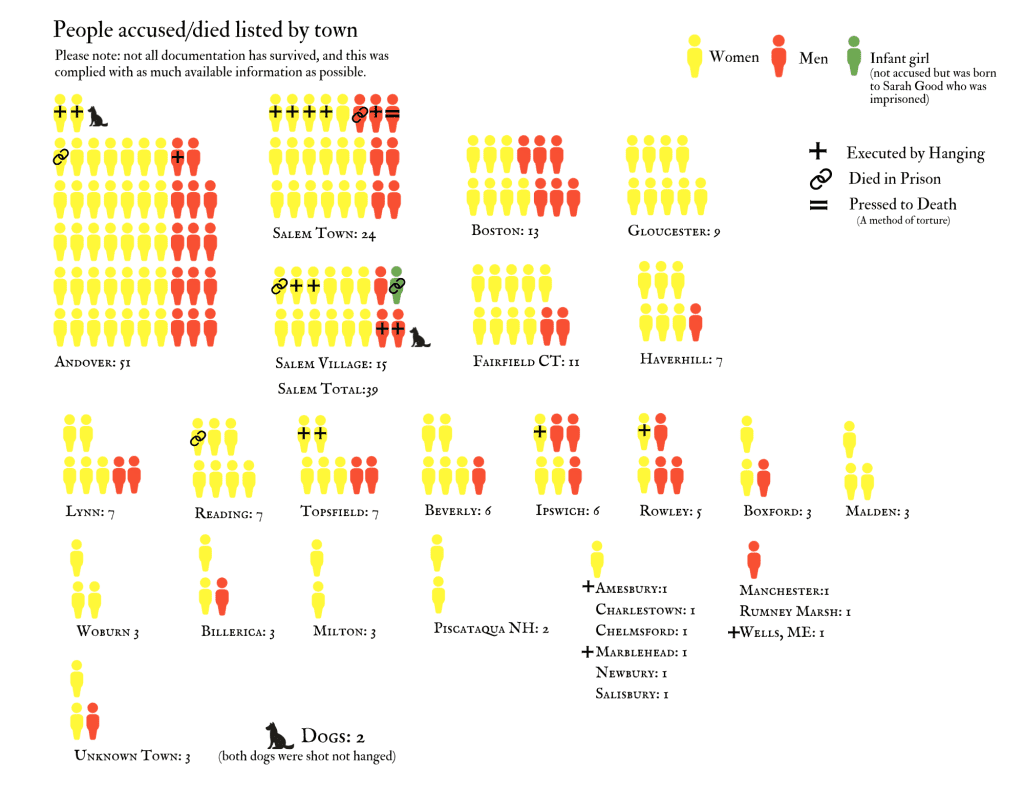

WHO was accused?

Contrary to popular belief, the witch trials extended far beyond Salem and affected both men and women across dozens of communities. This chart reveals the true geographic scope of the 1692 crisis, showing accusations and deaths across 25+ towns throughout Essex County, Massachusetts, and southern Maine. While women comprised approximately 80% of the accused, men represented a significant minority—challenging the common misconception that only women were targeted. The chart also illustrates the varied outcomes: some communities saw executions (marked with crosses), while others experienced deaths in prison or by torture. Even two dogs were accused and killed, highlighting the extent of the hysteria that gripped the region.

The data reveals striking patterns: Andover experienced the highest concentration with 51 people accused or killed, with entire families targeted including several children. Salem (combining Salem Town and Salem Village) had 39 cases total, demonstrating that even Salem itself accounted for only about 20% of all accusations across the region.

The Ripple Effect

The accusations followed predictable patterns of social networks, family connections, economic rivalries, and community boundaries. Neighbors accused neighbors, family disputes escalated into witchcraft charges, and longstanding grudges found new expression through supernatural allegations. The geographic spread reveals how the crisis exploited existing fault lines in Puritan society: urban versus rural tensions, generational conflicts, property disputes, and religious factional disagreements.

#1 Witch Trials Memorial (Charter Street)

The Witch Trials Memorial is often confused as the place of execution or the burial place for the victims of the Witch Trials, likely due to its proximity to the Old Burying Point (Charter Street Cemetery). This design, created by Maggie Smith and James Cutler, of Bainbridge Island, Washington, was chosen from a public competition of 246 entrants. The memorial was first presented by renowned playwright Arthur Miller, author of The Crucible, on November 14, 1991, and then dedicated on August 5, 1992 by Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor, and author Elie Wiesel, who noted, “If I can’t stop all of the hate all over the world in all of the people, I can stop it in one place within me,” adding, “We still have our Salems.”

The Witch Trials Memorial is often confused as the place of execution or the burial place for the victims of the Witch Trials, likely due to its proximity to the Old Burying Point (Charter Street Cemetery). This design, created by Maggie Smith and James Cutler, of Bainbridge Island, Washington, was chosen from a public competition of 246 entrants. The memorial was first presented by renowned playwright Arthur Miller, author of The Crucible, on November 14, 1991, and then dedicated on August 5, 1992 by Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor, and author Elie Wiesel, who noted, “If I can’t stop all of the hate all over the world in all of the people, I can stop it in one place within me,” adding, “We still have our Salems.”

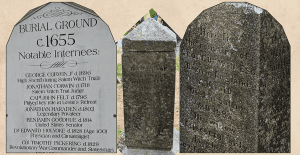

#2 Old Burying Ground /Charter Street Cemetery (Charter Street)

In the Charter Street Cemetery, you won’t find any of the victims of the Salem Witch Trials, but two significant figures from this dark chapter of history are interred here: John Hathorne and Bartholomew Gedney; both men played crucial roles in the trials as examining magistrates. (The charter street visitor center has maps that will help you find the two magistrates’ graves.)

Also buried in this cemetery is the second wife of Giles Corey; Mary Corey (alternatively spelled Corry on the stone) who died in 1684.

#3 Merchant Hotel (Washington Street)

On this site once stood the home of Sheriff George Corwin, a central figure in the Salem Witch Trials whose life became entangled with wealthy merchant Phillip English in a legal dispute that spawned colorful legends. During the hysteria of the trials, Phillip English and his wife Mary were accused of witchcraft. Unlike many others, their wealth afforded them the means to flee Salem until the trials subsided. Upon their return, they discovered Sheriff Corwin had confiscated their property. What followed was a lengthy legal battle; English initially sued Corwin and lost, but persisted with another lawsuit, where Corwin was found liable and arrested. Before the matter could be fully resolved, Corwin died unexpectedly at just 30 years of age, still indebted to English.

Two dramatic rumors emerged from this conflict:

- That English threatened to steal Corwin’s corpse and hold it for ransom until his debt was paid

- That the Corwin family, fearing such an act, secretly buried the sheriff in their basement while placing an empty coffin in the family tomb at Broad Street Cemetery

Despite the persistence of these stories, historical records provide no evidence that either event actually occurred. While English may have made such threats in the heat of their dispute, legal documents confirm that no body-snatching took place. These embellishments illustrate how readily historical conflicts transform into folklore, particularly when connected to the already sensational events of the Salem Witch Trials. George Corwin is buried in the Corwin family plot in the Broad Street Cemetery.

#4 Judge Hathorne’s Home Site (Lappin Park)

The relationship between the writer Nathaniel Hawthorne and his ancestor, Judge John Hathorne; the Salem witch trials magistrate, is often misunderstood. Despite the spelling difference in their surnames, both names were pronounced identically—like the “Hawthorne tree.” Spelling variation wasn’t unusual for a period of time, as standardized spelling had not yet been established. In a time when formal education wasn’t universal, people typically spelled names phonetically, resulting in numerous variations of the same family name appearing in written records.

The Hawthorne family name evolved over generations, from the original “Hathorne” to “Hawthorne” and a few other variations. A common misconception is that Nathaniel deliberately added the “W” to distance himself from his infamous ancestor. More likely, the addition served to clarify pronunciation rather than to hide his lineage. If true disassociation had been his goal, a complete name change would have been more effective, especially considering Nathaniel was already a recognized figure in Salem during his lifetime.

Far from hiding his ancestry, Hawthorne directly addressed it in his writings. In the introduction to “The Scarlet Letter,” he explicitly acknowledges his ancestor Judge Hathorne:

“His son, too, inherited the persecuting spirit and made himself so conspicuous in the martyrdom of the witches that their blood may fairly be said to have left a stain upon him. So deep a stain, indeed, that his old dry bones, in the Charter Street burial ground, must still retain it, if they have not crumbled utterly to dust! I know not whether these ancestors of mine bethought themselves to repent and ask pardon of heaven for their cruelties, or whether they are now groaning under the heavy consequences of them, in another state of being. At all events, I, the present writer, as their representative, hereby take shame upon myself for their sakes and pray that any curse incurred by them—as I have heard, and as the dreary and unprosperous condition of the race, for many a long year back, would argue to exist—may be now and henceforth removed.”

This passage demonstrates that while Hawthorne felt the weight of his ancestor’s actions, he openly claimed the connection rather than attempting to obscure it.

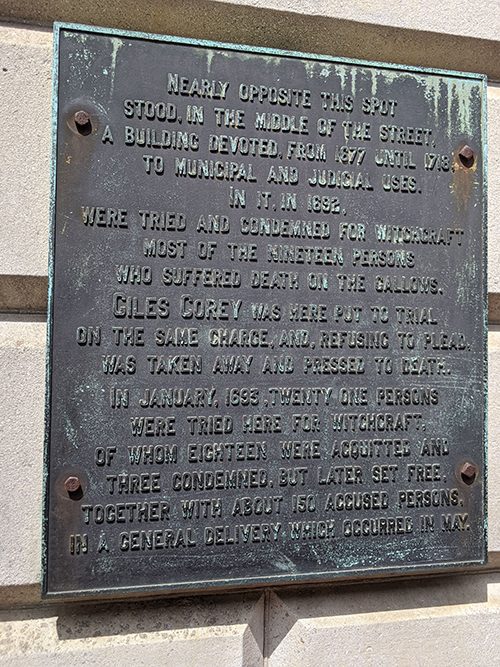

#6 The Town House and the Reality of Accusations in the Salem Witch Trials

The Town House originally stood in the middle of what is now Washington Street. It was here that the victims of the Salem Witch Trials were tried and convicted. The building served as Salem’s Town House until 1718, when another location was chosen on Essex Street.

Who Really Made the Accusations?

A common misconception about the Salem Witch Trials concerns who made the accusations. Nearly every movie or book places the blame entirely on “young girls,” but historical evidence tells a different story. This misconception partly stems from Arthur Miller’s play “The Crucible,” which portrays accusations being made by teenage girls.

When examining the actual court records of accusers and afflicted persons during this time period, a more complex picture emerges:

- Nearly 70% of the afflicted persons were over the age of 17, making the majority of them adults

- 82% of the afflicted were female

However, the afflicted individuals weren’t the ones who formally filed complaints with authorities. Court records reveal that of the 21 people who officially filed accusations at the Town House, 20 were adult men. These were typically family members acting on behalf of the afflicted.

These male family members would witness the afflictions of their daughters, wives, or other relatives, and then take legal action by filing formal accusations. Some men became responsible for multiple accusations, with Thomas Putnam Sr. being particularly prolific. As the father of Ann Putnam Jr. and husband of Ann Putnam Sr. (both afflicted), he personally filed accusations against 36 different people.

This pattern reveals how the witch panic operated through family networks and male authority. While the afflicted individuals provided the spectacle and testimony of bewitchment, it was primarily men who translated these experiences into the legal proceedings that led to arrests and trials.

Other common myths debunked

Method of Execution

In the Salem Witch Trials, the victims were executed by hanging, and were not burned at the stake like you might have believed. Why the confusion? It comes down to how witchcraft was classified under the law. In Salem, witchcraft was considered a crime against the government (a capital crime), and English law said the punishment for such crimes was hanging. Meanwhile, in many European countries with strong Catholic influence, witchcraft was treated as heresy – a religious crime against the Church, and the punishment for heresy was burning at the stake. Salem’s proceedings, while certainly influenced by religious beliefs, operated within a civil legal framework, whereas many European trials were conducted under heavily church-influenced legal systems where religious doctrine more directly determined punishment methods.

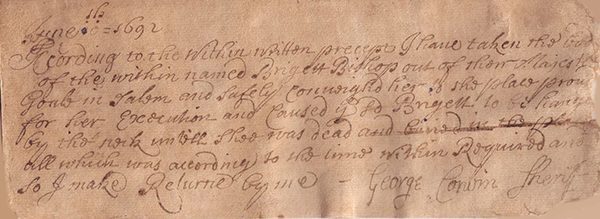

Transcription edited into modern English

“June 10th — 1692

According to the within written order (‘within’ is referring to the warrant document), I have taken the body named Bridget Bishop from their Majesties’ Jail in Salem and safely conveyed her to the place provided for her execution and caused the aforesaid Bridget to be hanged by the neck until she was dead, [and buried in the same place] all which was according to the time within required, and so I make this report by me George Corwin Sheriff.”

The Crucible fact vs fiction

While Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible depicts a passionate affair between John Proctor and Abigail Williams as the central catalyst for the Salem witch trials, historical records reveal this to be a significant fabrication. Miller, who conducted research in Salem, deliberately altered historical facts to create a more compelling parallel to the McCarthy hearings of the 1950s.

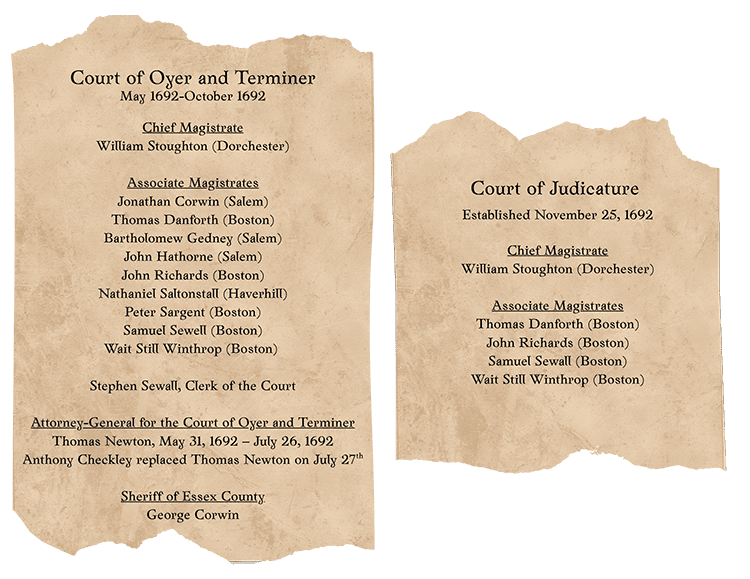

Historical evidence shows that John Proctor was approximately 60 years old during the Salem witch trials of 1692, while Abigail Williams was merely 11 years old. No documentation or testimony from the period suggests any interaction between them, let alone the intimate relationship portrayed in the play. The considerable age gap—nearly fifty years—further underscores the historical implausibility of such a connection. Beyond this central fabrication, Miller made another significant alteration for dramatic purposes: he reduced the number of magistrates (judges) from nine to two.

In reality, nine men presided over the witch trials, with court sessions requiring at least five be present for official proceedings. Miller condensed them into the characters of Judge Danforth and Judge Hathorne. While this simplification made the play more manageable for audiences, it also concentrated responsibility and villainy onto fewer characters, particularly Judge Hathorne, who often appears as the primary antagonist. This dramatic compression obscures the historical reality that the trials’ injustices were perpetrated by a larger group of officials, distributing both the responsibility and the blame across multiple individuals rather than focusing it on a single villain.

The truth will NOT set you free

A common misconception suggests that people who confessed to witchcraft in Salem were immediately freed. This myth doesn’t hold up to historical scrutiny. While most confessors did survive the trials they may have been kept in jail for a specific strategic reason. Once someone confessed, they became valuable to authorities as potential witnesses against other accused “witches.” The courts kept confessors alive because their testimony could help convict others. Several confessors actually had execution dates scheduled, but these never took place, because when the courts were restructured following complaints from victims’ families and influential community members, all pending executions were suspended. During later proceedings, many confessors revealed they had only admitted guilt under extreme duress or because they believed confession might lead to leniency. This helped to expose the flawed nature of the original court of Oyer and Terminer. So while confession did typically prevent execution, it led to continued imprisonment rather than freedom – a crucial historical detail that corrects the oversimplified version of events often repeated today. The only confessor to be executed was Samuel Wardell who was executed on September 22nd, 1692.

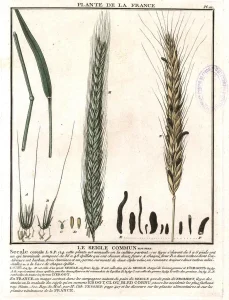

“Moldy Bread” & The LSD connection

The ergot hypothesis, popularized by Linnda Caporael in the 1970s, suggested that ergot-contaminated rye might have caused the hallucinations and convulsions that led to the witch trial accusations. This theory gained particular attention during the 1970s partly because LSD—a synthetic derivative of ergot alkaloids—was still prominent in public consciousness following the psychedelic era of the 1960s. The connection between ergot and hallucinogenic experiences made the theory seem plausible to many. However, this theory has significant problems:

The Puritans were experienced farmers who would have recognized ergot – the dark, horn-like fungal growths that replace rye kernels. These growths are quite visible and differ greatly from normal healthy grain. Given that ergotism was a known medical condition by the 17th century (Previously known as St. Anthony’s Fire; German physician Wendelin Thelius identified the link between the ergot fungus and epidemics in 1596, which was later definitively confirmed in 1676) and the Puritans were generally well-educated and informed about such matters, they would likely have identified and avoided contaminated grain. Additionally, ergot poisoning typically affects entire communities sharing the same food supply, but the Salem afflictions were selective, then targeting specific individuals rather than households eating from common grain stores.

The clinical reality of ergot poisoning is far more severe and distinctive than what was observed in Salem in 1692. Ergot alkaloids cause vasoconstriction (the narrowing of blood vessels, reducing blood flow, and increasing blood pressure) so severe that it leads to gangrene – the characteristic “St. Anthony’s Fire” burning sensation as extremities literally die from lack of blood flow. Historical accounts of ergotism describe people losing fingers, toes, hands, and feet to blackened, gangrenous tissue death. The convulsive form of ergot poisoning involves violent, sustained seizures and muscle spasms, not the intermittent episodes described during the Salem Witch Trials.

Numerous historians and psychologists were quick to debunk this theory in the 1970s and continue to poke holes in it today, yet the myth still persists.